Every Joynt and Member III

JP2, Benedict XVI, and Francis on the Civilization of Love

This is part three of my highly selective narration of moments and texts surrounding the Roman Catholic reckoning with other religions and global Catholicism after Vatican 2 and Nostra Aetate. I have two more installments planned of a more historical and philosophical nature focusing on Raymond of Llull and Nicholas of Cusa: what their metaphysics of religion was and what we can do with it.

The significance of Nostra Aetate and what followed from it is not reducible to an abstract set of theological positions. The real weight of the shift came from building relationships, physically visiting locations that are sacred to other religions, and establishing institutional connections with centers of worship and learning that previously did not exist. And the shift toward other religions was also a shift toward discussions of humanism and politics since, in the end, religion and politics cannot be treated as hermetically sealed separate spheres.

To take one example, in 1986 after an assassination attempt on the Prime Minister of India, Pope John Paul II did not merely make a speech from the Vatican. He traveled to Delhi, the very site of the attempt, and gave a speech commending the legacy of Mahatma Gandhi. Nor did he confine himself to saying, as would have been perfectly appropriate, that the imago dei demands human dignity for all men and women–he expressed praise for Gandhi with the words of another Indian luminary, Jawaharlal Nehru: “The light that shone in this country was no ordinary light.” JP2 even spoke of himself as a pilgrim paying homage to the way Gandhi drew on Hinduism andunderstood the significance of spirit and Satyagraha, the force of truth beyond physical violence. He held Gandhi up as a proponent of a “civilization of love”, the very phrase Pope Benedict XVI would later use to define the overarching goal of Catholic Social Teaching.

John Paul II was also, famously, the first pope to enter a mosque. The Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, one of the oldest in the world, also holds the tomb of St. John the Baptist. Thus it was no abstract ecumenism, but a religious and political need for all of us to approach the sacred sites and objects of our traditions that motivated this choice. Ecumenism does not rely on a general hope that people will be “nice”, it is the realistic demand born from sober reflection that the ground we live on, the buildings we inhabit, and the places we worship, and the cemeteries we bury our parents and children in, cannot be neatly separated from those of our neighbors. There simply is no other alternative. There is only peace-making. And so, John Paul II went to Damascus and prayed in a mosque. All of his actions were perfectly coherent as part of his pilgrimage following the path of the Apostle Paul (also visiting Greece and Malta on this trip).

John Paul II had met with groups of young people many times but in 1985 he met with Muslim youth for the first time in Morocco. It was also the first time a pope had traveled to speak in a Muslim-majority country at the invitation of its leader, in this case King Hassan II. JP2 gave a speech that called for global solidarity while also decrying the political and economic isolation imposed on the Global South by the North. He also decried the desiccation caused by losing the sense that we are spiritual beings oriented toward the Divine, a sense that followers of Islam clearly share with Catholics. His vision of solidarity was not the imposition of a homogeneous commodified culture, it was the vision of Pentecostal equality and unity within diversity. Every head aflame with one spiritual fire, every tongue speaking its own language. And again, he does not hesitate to say that these Moroccan Muslim youth are also ready to build the civilization of love by seeking the Most Beautiful Names of God.

“The world is as it were a living organism; each one has something to receive from the others, and has something to give to them.

I am happy to meet you here in Morocco. Morocco has a tradition of openness. Your scholars have travelled, and you have welcomed scholars from other countries. Morocco has been a meeting place of civilizations: it has permitted exchanges with the East, with Spain, and with Africa. Morocco has a tradition of tolerance; in this Muslim country there have always been Jews and nearly always Christians; that tradition has been carried out in respect, in a positive manner. You have been, and you remain, a hospitable country. You, young Moroccans, are then prepared to become citizens of tomorrow’s world, of this fraternal world to which, with the young people of all the world, you aspire.

I am sure that all of you, young people, are capable of this dialogue. You do not wish to be conditioned by prejudices. You are ready to build a civilization based on love. You can work to cause the barriers to fall, barriers that are due at times to pride, but more often to man’s feebleness and fear. You wish to love others, without any limit of nation, race or religion.”

Pope Francis also visited Morocco in 2019 at the invitation of King Mohammed VI, building on this previous connection. The fruits of these visits, especially for Roman Catholics, are not restricted to learning from other traditions or even teaching others more about our own. In a global church, the ability for a pope to visit Morocco and make a pastoral visit to the 33,000 African Catholics who live there is not an academic exercise. Ecumenism and interreligious sincerity is an exigency, especially in regions where Christians face violent persecution (I think especially of Nigeria). Because of the material and political realities of the world, pastoring a global Church, with communities in every continent, sharing markets and dwellings and cities and fields and businesses and streets and child-care, with sometimes radically different religious traditions means the labor of ecumenism and politics. The popes, bishops, and academics who engage in this theological and institutional work are not a replacement for more difficult questions of geopolitics, postcolonialism, and political economy, but they are a necessary framework for accomplishing those larger tasks in a way that leads to lasting peace. If the “reality” of law and order, peace and justice, can be seen as largely unrelated to questions of theology, worship, and spiritual practice, then we reveal ourselves to be methodological atheists and the “peace” we seek is simply another word for control and pacification. True peace is more difficult, more agonistic, demands more from us than physical force can give, though it may require all the blood our body can provide. It is the only alternative to what Radical Orthodoxy aptly names the “ontology of violence.”

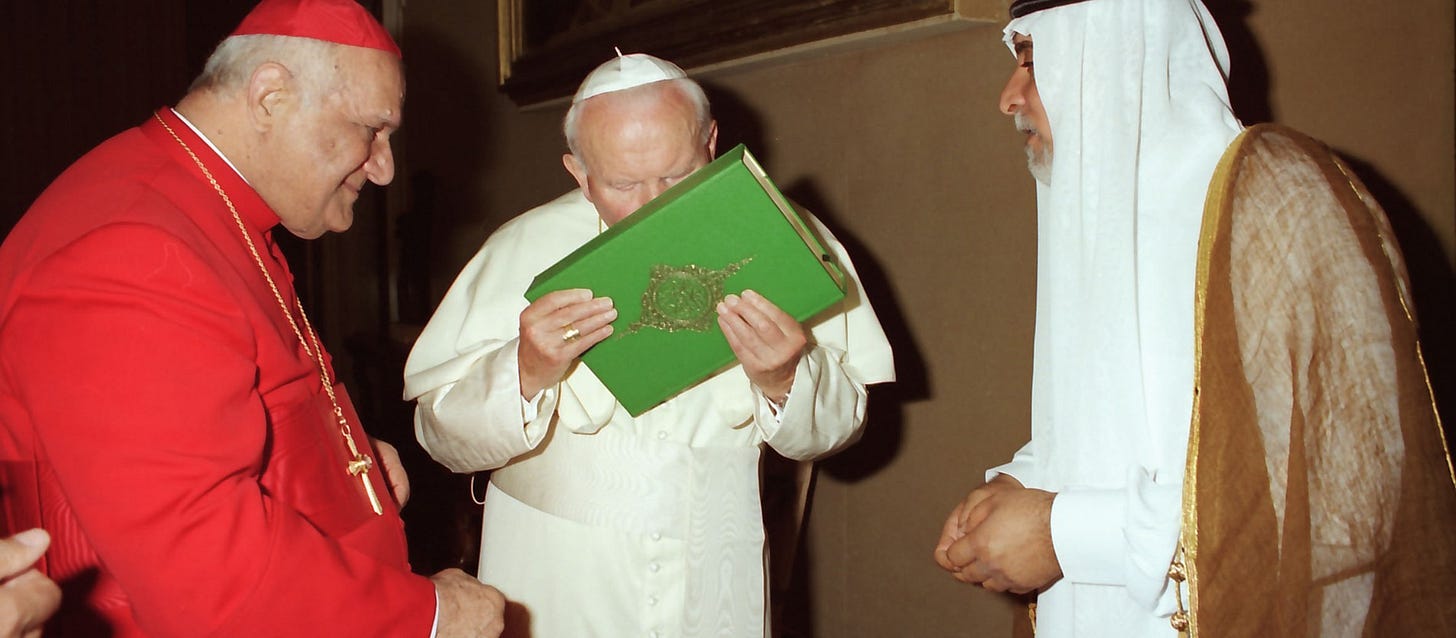

It is in this context of peaceful agonism that we can most fruitfully look at two of the more famous moments in Islamic-Catholic dialogue in last few decades: first, in 1999 when John Paul II kissed the Koran while receiving a delegation of Shiite and Sunni Muslims, the Chairman of the Iranian Ministry of Religion, and the Archbishop of Baghdad, Raphael I Bidawid. A Koran was given to JP2 as a gift and he reverentially kissed it.

There was a fierce backlash in some Catholic circles and it immediately became a paradigmatic instance, a powerful weapon in the arsenal of reactionaries. Taylor Marshall, to name one prominent online reactionary voice, continues to point to this moment as illuminating the bankruptcy of the post-Vatican 2 church and the papacy of JP2 as a kind of paste-board Catholicism, colorfully decorated with nothing inside. The reader may deduce that I do not share this reaction; though, no one should be surprised that this event and photo produced some confusion and perhaps even pain among some of the lay faithful. But putting aside notions that this moment meant a dissolving of distinctions between religious traditions, we can embrace this pain as that ache which attends sudden growth in a child’s limbs. No pope had ever done something like this before, it was an action and a visual that startles, even today. And now that we have passed the 60th anniversary of Nostra Aetate, I do not think it is controversial to say that, at least at the parish level in the United States, we have failed to explore concretely the meaning of the Church’s relationship to Islam beyond simple toleration.

Catholic parishes certainly have more pressing material concerns than crash courses in religious studies, but more could have been done by lay Catholics to form institutional and educational networks. As a resident in Michigan, I think there are opportunities for fruitful Catholic-Islamic relationships in Ann Arbor, Detroit, and of course Dearborn. Simply living together, learning languages, and extending networks of material support are how the best Islamic-Catholic (and Catholic-Jewish) relationships of previous eras emerged, it is no different now.

The second incident, Pope Benedict XVI’s 2006 Regensburg Address on faith, reason, and universities also induced pain. This time, not among conservative Catholics, but among Islamic political and religious leaders around the world. The address was a disaster for Catholic-Islamic relations. For context, I am a great personal admirer of Ratzinger’s theology and his pontificate and I bear no personal animus against him or his thought (quite the opposite). Yet even to me, it seems that focusing on the quotation of Manuel II Paleologos in his characterization of Islam as the root of the offense is somewhat missing the mark. Pope Benedict, of course, clarified that those were not his personal words or attitudes. The real difficulty is, I think, in Ratzinger’s history of Greek philosophy, the concept of the logos, and how these relate to biblical faith and religious violence as it is narrated in the address. In Ratzinger’s zeal to combat Harnack and undo the damage of the Hellenization thesis (a zeal I share), he framed the most undesirable aspects of the Scholastic tradition as sharing the metaphysics of Islam. That is, he pinpoints voluntarism as the great danger posed by Scotus and Ockham and identifies that structure with the metaphysics of Ibn Hazm. By narrating Scholastic voluntarism as the rejection of the logos and other Scholastic approaches (Aquinas, Bonaventure) as making logos rather than arbitrary will the nature of God a simplification takes place. Historical acts of religious violence are subtly associated with having the wrong metaphysics. And while the temptation to the wrong metaphysics (voluntarism) is narrated as having been rejected in Christian European Scholasticism, the reader and listener of the address is given to believe that Islam in general and as a religion simply has this voluntarist metaphysics. Therefore, they must also have an endemic problem of religious violence related to their voluntarist metaphysics. This is what leaders of Islamic universities, countries, and mosques around the world contested and were wounded by. It is also, as a more pedantic matter, not an accurate accounting of the varieties of mainstream Islamic metaphysics, especially their relationship to Greek philosophy and Neoplatonism in particular. Why Ibn Hazm (whose labeling as a simple voluntarist is also questionable to me) was chosen as the representative example of Islamic metaphysics and not the treasures of the far more influential Al-Ghazali baffles me.

The answer to this pain and misunderstanding was not withdrawal, but more engagement. Pope Benedict XVI, as a man deeply committed to the work of interreligious dialogue, did not shrink from further meetings and encounters between Catholics and Muslims. There is no other way forward. By the end of his papacy, Pope Benedict had actually entered even more mosques than John Paul II (who had visited several but only entered one): the Hussein Bin-Talal Mosque in Amman, Jordan and the famous Blue Mosque in Istanbul. Ecumenical agonism means saying what we fear as well as what we admire about each other and continuing the conversation even when it is difficult.

The controversy around the Regensburg Address, through the grace of God, bore even greater ecumenical fruit in A Common Word, a Christian-Muslim open letter on the consonance between the traditions. It even led to a conference in Jordan on the theme of Love in the Koran. These locations, these conversations, these people, were stirred to action by the intended and unintended consequences of Nostra Aetate. Rowan Williams (Archbishop of Canterbury at the time) and Pope Benedict himself commended the project.

Pope Francis and Pope Leo XIV continued this Catholic-Islamic project by joining the Vatican more closely with the great Islamic university in Cairo, Al-Azhar and its current Grand Imam, Dr. Ahmed Al-Tayeb. Pope Francis was crucial in solidifying this relationship. By speaking at Al-Azhar in Cairo in 2017 and by signing the Document on Human Fraternity with the Grand Imam Al-Tayeb in 2019, the Vatican made a gesture of respect for one of the most influential and prestigious institutions of Islamic learning that did not go unnoticed. In his 2017 speech, Pope Francis spoke beautifully of the concrete history of Egypt in this context: a land of civilizations and covenants. And, condemning any facile syncretism, Pope Francis reminded us of the Wisdom which seeks tirelessly for the One who transcends us and who meets us:

“From ancient times, the culture that arose along the banks of the Nile was synonymous with civilization. Egypt lifted the lamp of knowledge, giving birth to an inestimable cultural heritage, made up of wisdom and ingenuity, mathematical and astronomical discoveries, and remarkable forms of architecture and figurative art. The quest for knowledge and the value placed on education were the result of conscious decisions on the part of the ancient inhabitants of this land, and were to bear much fruit for the future. Similar decisions are needed for our own future, decisions of peace and for peace, for there will be no peace without the proper education of coming generations. Nor can young people today be properly educated unless the training they receive corresponds to the nature of man as an open and relational being.

Education indeed becomes wisdom for life if it is capable of “drawing out” of men and women the very best of themselves, in contact with the One who transcends them and with the world around them, fostering a sense of identity that is open and not self-enclosed. Wisdom seeks the other, overcoming temptations to rigidity and closed-mindedness; it is open and in motion, at once humble and inquisitive; it is able to value the past and set it in dialogue with the present, while employing a suitable hermeneutics. Wisdom prepares a future in which people do not attempt to push their own agenda but rather to include others as an integral part of themselves. Wisdom tirelessly seeks, even now, to identify opportunities for encounter and sharing; from the past, it learns that evil only gives rise to more evil, and violence to more violence, in a spiral that ends by imprisoning everyone. Wisdom, in rejecting the dishonesty and the abuse of power, is centred on human dignity, a dignity which is precious in God’s eyes, and on an ethics worthy of man, one that is unafraid of others and fearlessly employs those means of knowledge bestowed on us by the Creator.”