Faces Within Faces

R. Ezra ben Solomon's Commentary on the Song of Songs

Priot to the Zohar, the commentary on the Song of Songs (c.1245) by Rabbi Ezra ben Solomon of Gerona constitutes the most important kabbalistic treatment of that book of the Bible. In this text, the medieval Catalonian sage redeployed the riches of the entire midrashic and Talmudic exegetical tradition he had absorbed. The distinctively Kabbalistic dimensions he perceived in the Song of Songs were inextricable from that classical rabbinic inheritance. Even his Kabbalistic developments had precedent in some Jewish circles, though to what extent remains unclear and contested. In any case, the fundamental core of his exegesis is thoroughly steeped in rabbinic methods and topics, and as with almost every work of kabbalah, the text demands a high amount of facility with the formative writings of classical Judaism. In what follows, I simply want to point out a few moments from the introduction of the work and what kind of exegetical methodology and historical self-understanding he is using–the entire work is stunning and can be purchased here for a relatively reasonable price.

R. Ezra presents himself as standing within and receiving a tradition of insight which extends from Sinai through the prophets and the Sanhedrin to the masters of the Mishnah. R. Akiva and his companions are especially praised and exalted as those who entered Paradise and gained understanding of the mystery of the merkavah. Yet, despite his reverence for his tradition, at the same time, R. Ezra describes community of faith as living through a crisis. Not only has the temple been destroyed, causing his people to live in exile and precarity, even their religious knowledge has become dimmed, their exegetical abilities have dulled. His language becomes stark.

Wisdom was lost and with it the Torah.

No one knew its interpretation and subtleties,

Exegesis and the reasons for its commandments.

For a powerful connection exists between this wisdom

And the commandments’ meanings,

The Torah’s interpretation and the words of tradition,

Many passages of Scripture being based on it.

He blames interpreters who possessed “neither wisdom nor insight” and diminished Scripture even to the point of making Israel live “without the God of truth”, that is, without appropriate instruction in exegesis and the divine mysteries. Until his fiftieth year, R. Ezra says he kept silent about this until he could stand it no longer and began his commentary on the most precious book of all: the Song of Songs. The things contained in the Torah and that the sayings of the rabbinic sages contained have always been available but are purposefully obscure to protect them from those without desire, or without the pure forms of desire. R. Ezra does not think of himself as pursuing a novel activity, instead he states “I have interpreted it as I have received from our rabbis. I have crowned it with the meanings of the commandments and composed it in accord with the mysteries of creation.”

R. Ezra also mentions other approaches that he finds unacceptable or at least one-sided. First, those who read the Song of Songs as merely about physical desire, he condemns (though this is not a condemnation of physical eros or marriage or even erotic language mystically applied to the divine). Second, he accepts those who see in the Song of Songs a relatively simple allegory of God and Israel (or presumably God and the soul) but distinguishes his own reading from them. He says a third way, exegesis performed by those who have received the shekhinah and feel the full weight of R. Akiva’s statement that “the whole world cannot be compared to the day on which the Song of Songs was given to Israel” have something distinctive to offer. There is a way in which exegesis can become even more participatory than allegory (though it does not exclude allegorical readings). Reading the Torah can be a mystical labor that changes the world.

R. Ezra also assumes that what the Torah “is” is itself a profound mystery, vertiginous, and difficult to grasp. Any real exegetical insight must participate in the kind of theophany described at Sinai during the giving of the Law. Only in a theophanic spirit does the Torah reveal itself as revelation. Additionally, like Sinai, the Torah revealed itself according to the ability of each receiver, one way to Moses, another to Aaron, another to Nadab and Abihu, etc. These pluralities of reception are not obstacles to the unity of Truth, nor are they irreducible singularities that prevent communal reflection. They are “varied rungs…some more inward, some outward, some higher, some lower.”

In this way, the Torah comes forth from Sinai spreading into “seventy branches, the seventy faces of the Torah. These are the multiple meanings of its verses, ever changing and transmuting in every direction…” The living character of revelation, its fiery motion makes the oral tradition and historical community of interpreters absolutely essential for the functioning of religious practice. Far from destroying the need for halakah or legal judgements, it presupposes them and grounds them in a theological and metaphysical paradigm: the very character of revelation.

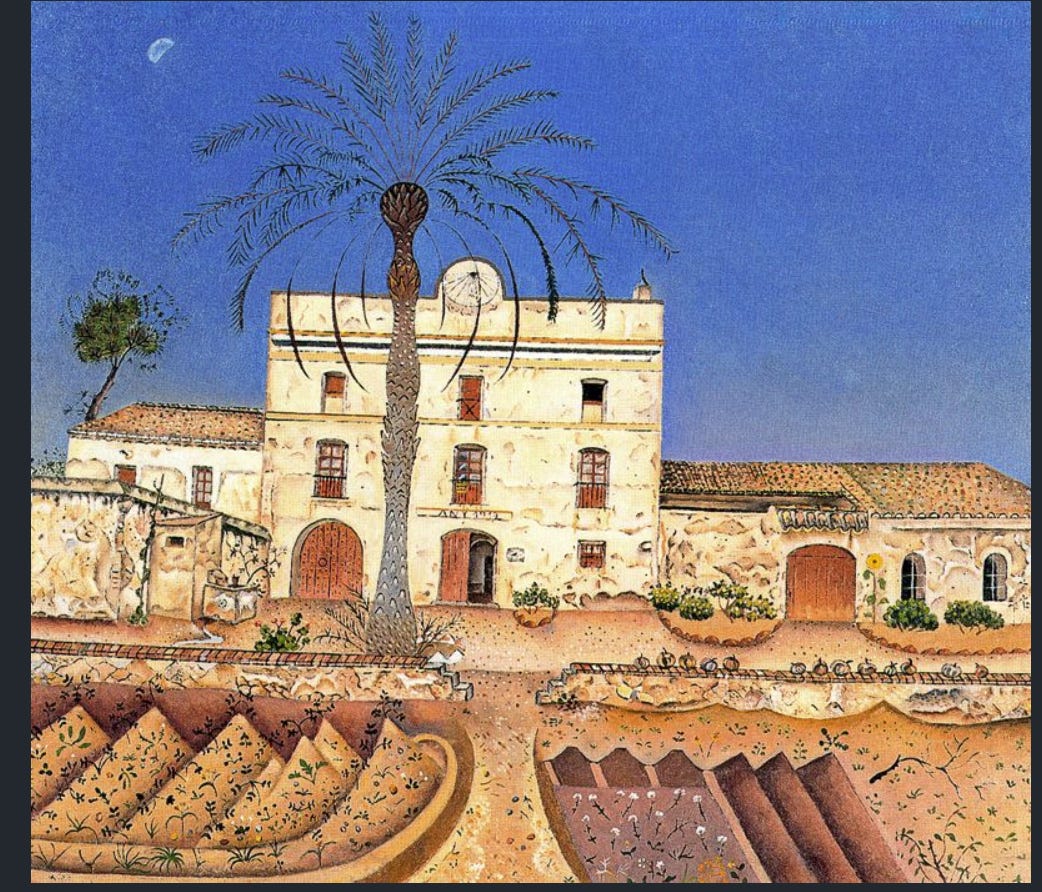

R. Ezra’s primary insight is that the Song of Songs is about creation. This is a reading that can certainly sustain additional readings of the Song of Songs as God pursuing Israel throughout salvation history yet it pushes those readings to unite history with the most primordial realities. R. Ezra begins with the mystery that God establishes his Throne before and during the six days of Creation. This is, of course, a reference to the passages in the Bereshit Rabba that outline the various pre-existent entities, including the divine throne. It also seems to be relying on the midrashic traditions of continuing creation (eg. the creation is not fully completed until the construction of the tabernacle, or the temple, etc). In one sense, creation emerges from God’s throne, in another sense, it is God’s throne.

And into this Throne, God placed the two fawns mentioned in Song of Songs 4:5, which are to be understood as Adam and Eve, the First Parents. An Evil One enticed these fawns away from the paradisaical state and salvation history is the history of the Shekhinah restoring us to Eden (albeit in a new way). Those among the patriarchs and matriarchs who perceived and acted rightly were co-causes in restoring the divine presence to the world and restoring the branches of the sefirot to their proper arrangement. Jacob/Israel in particular plays a dramatic role: his image was inscribed on the divine Throne before the world came into existence. Jacob is made worthy of a new vision through the education he received through Abraham and Isaac (an oral tradition and apprenticeship passed down through the descendants of Noah).

Jacob is favored above the patriarchs in receiving the glory of the Shekhinah in a unique way. Here we should think of the unparalleled mystical adventures that the Hebrew Bible ascribes to him: wrestling with a mysterious divine figure, sleeping in the House of God and seeing a ladder full of angels ascending and descending. Something is different about Jacob. At the same time, his status is not for himself alone, R. Ezra sees this new reception of the Shekhinah as revealing all three of the patriarchs, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, as constructing in their very selves the merkavah: the divine chariot-throne of God’s presence. It is crucial to note here that this is not some kabbalistic innovation. The idea that the patriarchs constitute the divine chariot is already present in classical midrashim like Bereshit Rabba 47 “Reish Lakish said: The patriarchs are themselves the divine chariot, as it is stated: “God ascended from upon Abraham,” “God ascended from upon him,” (Genesis 35:13) “And behold, the Lord stood upon him” (Genesis 28:13)”.

R. Ezra sees salvation-history and the Godhead as containing a series of correspondence and analogies, perhaps even mysterious identities. The divine Throne is both pre-existent and historically constituted by the three patriarchs. The twelve tribes of Israel are the narrative subjects of Kings and Chronicles and the reflections of divine numerated realities. The knesset Yisrael is on earth as it is in heaven. The crucial question, the quest which defines Judaism and the destiny of Israel as R. Ezra understands it, is contained in the dramatic theophany to Moses in the burning bush.

Israel’s fundamental question,

The essence of all mystical intentionality

And the mystery of faith,

Is this very query:

“What is His Name?”

It is the desire to know its origin,

The manner in which the name

Is bound to the Primal Cause.

In that holy place,

Moses received the knowledge of God,

Learning that the divine possesses three names

Composed of twelve letters,

Faces within faces, ten sefirot,

Existence within existences.

For R. Ezra ben Solomon, and the Kabbalists in general, the scorn and contempt for philosophy is really only a rejection of certain forms of philosophy: against any metaphysics that sees itself as autonomous and capable of bracketing the shape of the Godhead or deflating the mysteries of Sacred Scripture into more “understandable” categories. In actuality, the Kabbalists are practicing some of the most ambitious metaphysics of all time, ones that are wedded to the midrashic imagination, and every nook and cranny of the Hebrew Bible. The search for the Name of God becomes a journey at once exegetical, speculative, mystical, rational, and practical. Not only does this form of theology produce affective results, it relies on the affections as the very point of entry into the text and the power by which the divine realities are made more manifest. The most erotic book of the Bible is the holiest book of the Bible and our desire for the Godhead must enfold our entire selves in its utmost purity.

The secrecy and “esotericism” of Kabbalah is primarily concerned to defend the unassuming reader from her own ambiguous and undisciplined desires. Silence before certain topics concerning subjects that are easily misunderstood is not meant as a self-congratulatory form of elitism. This silence shares in the same reason we don’t speak about our greatest loves and desires or fears in front of those who we feel would not understand them–or even hold them in contempt. If we take R. Ezra as a master for reading the Bible, he can help us understand the intimacy that is possible through these divine words. It is an intimacy that both mirrors and simply is the nuptial union of God and Creation.

You cooked on this one fr